Cervical health is a cornerstone of a woman’s overall well-being (especially for women between the ages of 25 and 64). Yet many women are unaware of the critical role that routine screenings play in maintaining long-term health, or are put off by insufficient healthcare services and information, as well as psychological stress and cultural issues [1].

Cervical smear tests, also known as Pap tests or smear tests, are a simple yet powerful tool for detecting abnormalities in the cervix that could potentially lead to cancer. The screenings are primarily designed to detect changes in the cells of the cervix, which could develop into cervical cancer if left untreated [2][3][4].

These changes, often referred to as cervical dysplasia, may develop gradually and are not always accompanied by noticeable symptoms [5]. Cervical dysplasia is when cells on the cervix start to grow in an unusual way – often due to certain types of human papillomavirus (HPV), a common virus that can affect the skin and mucous membranes [5].

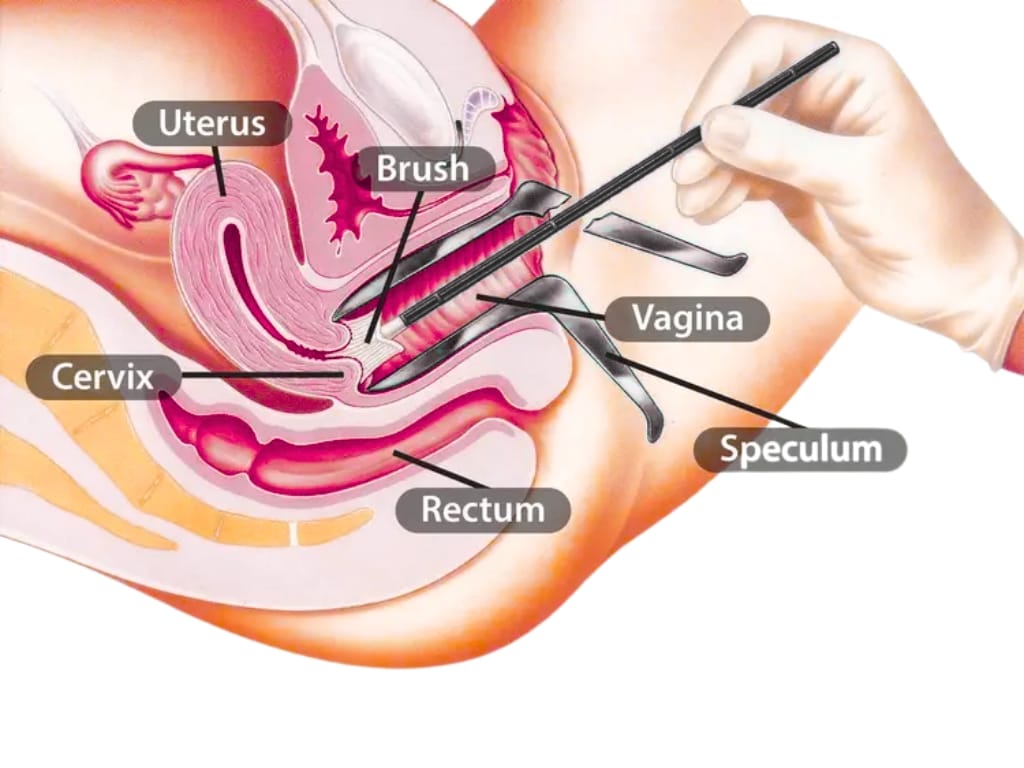

In spite of the barriers that exist, the test itself is simple: a healthcare professional collects cells from the cervix using a soft brush or spatula.6 These cervical cells are then examined, where they will be tested for the HPV virus. If high-risk HPV is found, the laboratory will test the sample for cell changes.7

But without regular screening, these abnormalities can go undetected for years, increasing the risk of progression to cervical cancer. So, here are five clinically-evidenced reasons why regular cervical smear tests should be an essential part of every woman’s healthcare routine.

Protect your health – schedule a cervical screening today.

1. Detecting Abnormalities

Early detection is crucial because cervical abnormalities do not automatically mean cancer. Many abnormal cells can be treated or removed before they become dangerous.

Robust evidence supports the value of cervical smear tests in detecting cell abnormalities that precede cancer, with a range of studies confirming high specificity [8]. For this, the Pap test remains the most available and feasible method for screening the cervix and detecting cervical dysplasia [9] – abnormal cell growth most commonly triggered by persistent infection with high-risk HPV strains.

Cytological examination doesn’t just spot dangerous changes; it allows for intervention long before invasive cervical cancer develops. In fact, more than 90% of cervical cancers show evidence of HPV infection and are preceded by detectable abnormal cells [10], so identifying these changes is a vital step in preventative care.

With the introduction of additional molecular techniques – such as immunostaining for cell cycle proteins (Mcm5 and Cdc6) [11] – recent studies have further improved the efficiency of abnormal cell detection [11][12]. For example, the immunoenhanced Pap test detected abnormal cells in all 28 clinically verified cases and reduced the false negative rate compared to conventional cytology [13], demonstrating particular value in picking up early-stage high-grade lesions that might otherwise be missed.

Digital advances also contribute; the use of AI has markedly improved the accuracy and efficiency of abnormal cervical cell identification, promising faster, more reliable screening in the near future [14]. Even before, screening has been associated with a 70% reduction in cervical cancer mortality in developed countries since its inception [15].

2. Preventing Cervical Cancer

One of the most compelling reasons for regular cervical smear tests is their role in preventing cervical cancer, a condition that develops slowly, often beginning as precancerous changes in the cervix that may go unnoticed for years. Without routine screenings, these early warning signs could be missed entirely, leaving women unaware of their risk until it becomes more serious.

Regular cervical smear tests provide a critical opportunity to catch these precancerous changes before they evolve into cancer. It is estimated screening can prevent over 7 in 10 cervical cancers [16]. This is because when abnormalities are detected early, healthcare providers can intervene promptly with treatments that remove or destroy the affected cells. These interventions are typically highly effective, drastically reducing the likelihood that cervical cancer will develop [17].

Early intervention for precancerous changes can include treatments such as cryotherapy, laser therapy, or excisional procedures like a cone biopsy. These treatments are highly effective in preventing the development of cervical cancer, particularly when the abnormal cells are identified at an early stage.

Early identification may also reduce the need for more invasive procedures later. In best-case scenarios, women can avoid the physical, emotional, and financial challenges associated with advanced cervical cancer treatment.

This type of cervical cancer prevention is particularly significant because cervical cancer often has no symptoms (asymptomatic) in its early stages. Women may feel completely healthy while abnormal cells are forming [18]. Smear tests act as an early warning system, helping women stay ahead of potential health threats.

A study in The Lancet from 2020 forecasted the WHO’s cervical screening targets and found that by scaling up twice-lifetime screening and cancer treatment, we could reduce mortality by 34.2%, averting 300,000 deaths by 2030 [19]. It also found that scale-up of cervical cancer screening, in line with the WHO targets, would ensure that up to 50% of women would receive appropriate surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy by 2023, which would increase to 90% by 2030 [19].

In countries with organised cervical screening programmes, the rates of cervical cancer have already decreased dramatically, demonstrating the real-world effectiveness of regular screening and early intervention.

For example, a study in the US between 1976 and 2009 identified a significant decrease in the incidence of early-stage cervical cancer, from 9.8 to 4.9 cases per 100,000 women. Late-stage disease incidence also decreased, from 5.3 to 3.7 cases per 100,000 women, too. Both trajectories were linked to the implementation of widespread Pap screening [20].

3. Improving Follow-Up Care

Cervical smear tests do more than detect abnormalities. They also provide a pathway to appropriate follow-up care. If an abnormality is detected, healthcare providers can guide women through the next steps, ensuring that any potential issues are addressed.

Follow-up care may involve additional testing, such as a repeat smear, HPV testing, or a colposcopy – a closer examination of the cervix using a specialised microscope. Depending on the findings, treatment options may include procedures to remove abnormal cells (like the aforementioned cryotherapy, laser therapy, or a cone biopsy). These interventions are typically highly effective at preventing the progression to cervical cancer [21].

In addition, identifying precancerous changes provides an opportunity for healthcare providers to discuss lifestyle modifications and other preventive strategies. For example, HPV vaccination, quitting smoking, and regular follow-up care can all help reduce the risk of cervical cancer and support overall cervical health. HPV vaccination, in particular, has been shown to cut cases of cervical cancer by 90%, according to figures in England [22].

The follow-up process also provides an opportunity for women to receive counselling and education about their condition. Understanding the nature of the abnormality, the risk factors involved, and the steps needed to maintain cervical health can empower women to take control of their own care.

In LMICs, cervical screening is a key touchpoint in providing disease education, with general knowledge on cervical cancer improving to 94.4% from 73% following the intervention [23] – evidence that supports can go beyond the here and now.

4. Increasing Quality of Life

Ultimately, cervical smear tests contribute to longer, healthier lives and improved quality of life for women. Women whose cervical abnormalities are caught early typically face less intensive treatment regimens, allowing them to maintain their daily routines and quality of life.

They are less likely to experience the emotional, physical, and financial burdens associated with late-stage cancer treatment. Beyond this, early detection and treatment reduce the likelihood that cancer will spread to other parts of the body, which is critical for long-term survival.

The impact of early detection extends beyond survival. Women who receive timely treatment often experience less pain, fewer hospital visits, and a reduced risk of long-term complications [24]. This means they can continue working, caring for their families, and participating fully in life with confidence and peace of mind.

Studies have demonstrated a substantial decrease in hospital admissions related to cervical disease, which may be partly explained by the success of cervical cancer screening programmes. By enabling early detection and timely management of precancerous lesions, screening reduces the progression to advanced disease, thereby decreasing the likelihood of hospitalisation [25].

These links translate from the fact that women who participate in cervical cancer screening have a higher health-related quality of life (HRQoL) than those who do not [26]. And many other factors also affect HRQoL – such as socioeconomic status and social circles [26] – cervical screening can arguably offer a strong foundation for overall outlook.

5. Tackling Stigmas

Despite the clear health benefits, many women continue to face emotional and social barriers that discourage them from attending cervical smear tests. These stigmas often create unnecessary anxiety and shame, preventing women from accessing a simple, preventive test that could save their lives.

But from a behaviour changes perspective, the more we social norm cervical screening, the more we can see it as a routine, responsible, and socially endorsed health practice, making women more likely to feel motivated to participate.

Similarly, normalising conversations about cervical health through education, community outreach, and public campaigns helps to create new, positive social norms. Healthcare providers can reinforce these norms by offering culturally sensitive, respectful care and by encouraging open discussion without judgment. Sharing stories from women who attend screening, as well as visible support from trusted community figures, strengthens motivation and perceived social acceptance.

Tackling stigma is about more than awareness; it is about creating an environment where cervical screening is seen as a standard act of self-care. By increasing capability through education, providing opportunities through accessible services, and fostering motivation through positive social reinforcement, women can feel empowered and supported to take charge of their cervical health.

Booking a Test With The Health Suite

Cervical smear tests are a simple yet powerful tool in maintaining women’s health. From the detection of abnormalities and prevention of cervical cancer to the identification of precancerous changes, they play a critical role in safeguarding long-term well-being.

At The Health Suite, our experienced gynaecological team offers two types of cervical screening:

- The standard cervical smear, which tests for HPV infection following the NHS screening guidelines

- A more detailed cervical smear, which tests for HPV infection and analyses cervical cells for abnormalities

By combining this clinical expertise and state-of-the-art technology with comprehensive patient education (such as ongoing support), we help to provide a proactive choice that empowers women to maintain their health, prevent serious disease, and live life to the fullest.

Prioritise your health and book a cervical screening with The Health Suite Leicester

Protect your health – schedule a cervical screening today.

References:

- Shariati-Sarcheshme M, et al. Women’s perception of barriers and facilitators of cervical cancer Pap smear screening: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e072954

- Sachan PL, Singh M, Patel ML, Sachan R. A Study on Cervical Cancer Screening Using Pap Smear Test and Clinical Correlation. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2018;5(3):337-341

- NHS. What is cervical screening? Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/tests-and-treatments/cervical-screening/what-is-cervical-screening/

- NHS. Why cervical screening is done. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/tests-and-treatments/cervical-screening/why-its-done/

- Cooper DB, McCathran CE. Cervical Dysplasia. [Updated 2023 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430859/

- NHS. What happens at your cervical screening appointment. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/tests-and-treatments/cervical-screening/what-happens/

- Cancer Research UK. What is cervical screening? Available at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cervical-cancer/getting-diagnosed/screening/about

- Chen C, et al. Accuracy of several cervical screening strategies for early detection of cervical cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22(6):908-921

- Najib FS, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Cervical Pap Smear and Colposcopy in Detecting Premalignant and Malignant Lesions of Cervix. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2020;11(3):453-458

- WHO. Human papillomavirus and cancer. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papilloma-virus-and-cancer

- Wang D, et al. The role of MCM5 expression in cervical cancer: Correlation with progression and prognosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;98:165-172

- Murphy N, et al. p16INK4A, CDC6, and MCM5: predictive biomarkers in cervical preinvasive neoplasia and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2005 May;58(5):525-34

- Williams GH, et al. Improved cervical smear assessment using antibodies against proteins that regulate DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998; 8;95(25):14932-7

- Liu L, et al. Performance of artificial intelligence for diagnosing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2024;80:102992.

- BMJ Best Practice. Cervical cancer screening. Available at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/1123

- The Eve Appeal. Cervical Screening. Available at: https://eveappeal.org.uk/information-and-advice/preventing-cancer/facts-and-tips-for-cervical-screening/

- Tierney B, et al. Early cervical neoplasia: advances in screening and treatment modalities. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2010;8(8):547-55

- NICE. When should I suspect a diagnosis of cervical cancer? Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/cervical-cancer-hpv/diagnosis/diagnosis/

- Canfell K, et al. Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):591-603.

- Yang DX, et al. Impact of Widespread Cervical Cancer Screening: Number of Cancers Prevented and Changes in Race-specific Incidence. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41(3):289-294

- Tomaszewski MJ, et al. Advances in ablative treatment for human papillomavirus-related cervical pre-cancer lesions. Gynecol Obstet Clin Med. 2024;1(2):e-0001.

- BBC. HPV vaccine stops 90% of cervical cancer cases. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cv2x2en4lpro

- Dedey F, et al. Assessing the impact of cervical cancer education in two high schools in Ghana. BMC Cancer. 2024; 6;24(1):1359

- Mumba JM, et al. Cervical cancer diagnosis and treatment delays in the developing world: Evidence from a hospital-based study in Zambia. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2021;37:100784

- López N, et al. Reduction in the burden of hospital admissions due to cervical disease from 2003-2014 in Spain. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018; 3;14(4):917-923

- Zhao M, et al. Healthy-related quality of life in patients with cervical cancer in Southwest China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Services Research. 2021;21:841